Simply Psych Community

Supporting Someone After They Leave a Toxic, Controlling Relationship

Ending a toxic, controlling relationship is a courageous act, but it often comes with a mix of relief, sadness, and guilt. If someone you care about has recently taken this brave step, your support can be a vital part of their healing journey. Below are some practical and empathetic ways to help:

1. Acknowledge Their Strength

Leaving a toxic relationship takes immense courage. Validate their decision by acknowledging their bravery. You can say something like:

"It took so much strength to put yourself first. I’m really proud of you for making this decision."

"I know this wasn’t easy, but it’s a step toward the life you deserve."

Affirming their choice helps counter the self-doubt and guilt they may be feeling.

2. Listen Without Judgment

Guilt often stems from the manipulative dynamics of the previous relationship, where they may have been made to feel responsible for their partner's behavior. Provide a safe space for them to express their emotions without fear of judgment.

Let them talk at their own pace.

Avoid offering advice unless they ask for it.

Reassure them that their feelings—no matter how complex—are valid.

3. Help Them Reframe Guilt

People leaving toxic relationships often feel guilty for “giving up” or “hurting” their partner. Help them reframe this guilt by focusing on their well-being:

Remind them that choosing their mental, emotional, and physical health is not selfish—it’s essential.

Normalize their guilt as part of the healing process, not as evidence they made the wrong choice.

Help them see that choosing not to be with someone they don’t feel connected to is ultimately kinder than staying in a relationship out of obligation.

You could say:

“It’s natural to feel guilty, but you didn’t cause the toxicity. Choosing yourself doesn’t mean you don’t care—it means you value your well-being.”

"Staying with someone when your heart isn’t in it would be unfair to both of you. Ending it allows both of you to move toward relationships that truly feel right."

"It makes sense that you feel this way. You’re a compassionate person, and it’s hard to see someone else in pain, even when you know it’s the right decision."

4. Encourage Self-Compassion

When someone feels guilty, they often engage in self-critical thoughts. Encourage them to treat themselves with the same kindness they would offer a friend in their situation. Help them practice self-compassion through:

Journaling about their strengths and the reasons they left.

Affirmations like, “I deserve to be treated with respect and kindness.”

Gentle reminders to focus on progress, not perfection.

5. Be Patient with Their Healing Process

The road to recovery is rarely linear. The person you are supporting might oscillate between relief and guilt or even consider returning to their former partner. Be patient and remind them of the reasons they left without being forceful or dismissive.

If they do express doubts or talk about reconciliation, try saying:

"It’s okay to have mixed feelings. But remember why you left and how far you’ve come."

"Let’s talk about what made you feel unhappy in the relationship. How does it feel to be free from that?"

6. Encourage Professional Support

If their guilt and emotional turmoil feel overwhelming, gently suggest professional help. A therapist can help them explore and process the dynamics of the relationship, build self-esteem, and develop coping strategies for moving forward.

7. Celebrate Their Progress

Help them focus on the positives of their decision. Celebrate milestones like rediscovering hobbies, making new friends, or simply feeling more at peace. These moments reinforce that leaving the toxic relationship was the right choice.

You might say:

"It’s great to see you smiling more."

"You’ve come so far, and I know you’ll keep growing."

8. Remind Them They Deserve Healthy Love

Toxic relationships often erode a person’s belief in their worthiness of love. Reinforce that they deserve respect, kindness, and mutual support in their relationships.

Simple reminders go a long way. For example:

"You deserve to be loved for who you are, without conditions or control"

"You have every right to prioritize your feelings and needs. It’s okay to step away when a relationship isn’t what you want. That doesn’t make you a bad person—it makes you honest."

Final Thoughts

Supporting someone who has left a toxic, controlling relationship requires patience, empathy, and encouragement. By being a compassionate presence, you can help them navigate the guilt, rediscover their self-worth, and begin the healing process. Most importantly, remind them that the decision to leave wasn’t just a step away from something harmful—it was a step toward a healthier, more fulfilling life.

This post was reviewed by a licensed mental health professional.

How to Support Someone with Fear of Abandonment

Fear of Abandonment

Fear of abandonment is a deeply human experience, rooted in our fundamental need for connection and security. At its core, it’s the fear of being left behind or unloved, often tied to early experiences of loss, neglect, or rejection. While it’s natural to feel uneasy about losing someone important, for some, this fear can run so deep that it shapes their relationships, behaviors, and even their sense of self. It might manifest as over-attachment, constant reassurance-seeking, or avoidance of intimacy altogether. Understanding the signs of abandonment fear is the first step to recognizing how it may be influencing someone's life and relationships—and, more importantly, how to provide appropriate support.

Signs that someone may have a fear of abandonment can vary from person to person, but here are some common indicators to look out for:

Clingy or dependent behavior: An individual with a fear of abandonment may exhibit clingy or overly dependent behavior in relationships. They may have a constant need for reassurance, seek excessive closeness, or have difficulty being alone.

Intense fear of rejection: People with a fear of abandonment often have an intense fear of rejection or being left behind. They may be hypersensitive to any signs of perceived rejection, leading to heightened anxiety or emotional distress.

Constant need for validation: Individuals with a fear of abandonment may constantly seek validation and approval from others. They may have a strong desire for external validation to feel secure and may struggle with self-esteem issues.

Difficulty trusting others: Due to their fear, individuals with abandonment issues may have difficulty trusting others. They may be suspicious or have a heightened sense of vigilance, constantly on the lookout for signs that someone might leave or betray them.

Overwhelming jealousy: Fear of abandonment can manifest as intense jealousy or possessiveness in relationships. The individual may feel threatened by any perceived attention or affection given to others and may engage in controlling behaviors to maintain a sense of security.

Avoidance of relationships or intimacy: Some individuals with a fear of abandonment may avoid close relationships or intimacy altogether to protect themselves from potential rejection or abandonment. They may isolate themselves emotionally or physically as a defense mechanism.

Fear of being alone: People with a fear of abandonment often have a strong aversion to being alone. They may go to great lengths to avoid being by themselves, seeking constant companionship or engaging in activities to distract themselves from feelings of loneliness or abandonment.

Excessive people-pleasing: Individuals with a fear of abandonment may engage in people-pleasing behaviors in an attempt to avoid rejection or abandonment. They may prioritize others' needs over their own, often sacrificing their own well-being to maintain relationships.

Emotional volatility: Fluctuating emotions and intense mood swings can be common in individuals with a fear of abandonment. They may experience heightened emotional reactivity, including feelings of anger, sadness, or anxiety, particularly in response to perceived threats of abandonment.

Self-sabotaging behaviors: Some individuals with a fear of abandonment may engage in self-sabotaging behaviors in relationships. They may push people away, create conflicts, or engage in self-destructive patterns as a way to test others' loyalty or to preemptively end relationships before they can be abandoned.

It's important to note that these signs are not definitive proof of a fear of abandonment, and a professional assessment is necessary. If you or someone you know is experiencing significant distress or impairment due to a fear of abandonment, it's advisable to seek support from a mental health professional.

How to Cope with Abandonment fears

Self-awareness: Start by recognizing and acknowledging your fear of abandonment. Understanding the source of your fear can be an important step towards addressing it.

Therapy or counseling: Consider seeking support from a mental health professional, such as a therapist or counselor. They can help you explore the root causes of your fear, develop coping mechanisms, and work towards overcoming it.

Build self-worth: Cultivate a sense of self-worth and confidence. Engage in activities that you enjoy and that help you feel good about yourself. Developing a positive self-image can help reduce dependency on external validation.

Practice self-care: Prioritize self-care activities that promote emotional well-being. This might include exercise, meditation, journaling, spending time with loved ones, pursuing hobbies, or seeking out activities that bring you joy and fulfillment.

Challenge negative thoughts: Learn to identify and challenge negative thoughts related to abandonment. Practice reframing these thoughts by focusing on evidence that contradicts them. Replace irrational fears with more balanced and realistic perspectives.

Build a support network: Surround yourself with supportive and reliable people who can provide emotional support. Strengthening your social connections can help alleviate fears of abandonment by creating a sense of security and belonging.

Communicate openly: Express your fears and concerns to trusted friends or loved ones. Open and honest communication can foster understanding, deepen relationships, and help alleviate anxieties.

Address past traumas: If your fear of abandonment stems from past traumatic experiences, consider addressing them through therapy or counseling. Processing past traumas can be instrumental in healing and reducing fear-related symptoms.

Develop coping strategies: Learn and practice coping strategies that help manage anxiety and fear. This might include deep breathing exercises, mindfulness techniques, or engaging in activities that promote relaxation and stress reduction.

Patience and self-compassion: Overcoming a fear of abandonment takes time, and setbacks are normal. Be patient with yourself and practice self-compassion throughout the process. Remember that personal growth and healing are journeys, and progress may come in small steps.

Therapy Goals for Individuals with Fears of Abandonment

Goals in therapy include developing a more stable self-image, improving self-esteem, decreasing mood reactivity, and increasing stability in relationships.

These goals are accomplished by exploring various techniques and skills for managing intense emotions and feelings. When working with people who struggle with abandonment issues (or attachment issues), the process is slow and progresses in stages until a true working alliance develops.

People with a fear of abandonment wish to merge or be close to others but also feel uncomfortable and paranoid when doing so--which can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy. That is, the person fearing abandonment may behave in ways that ultimately lead to being abandoned. This might include fits of rage, micro-psychotic episodes, splitting behaviors, projection, or self-harm behaviors.

People who have abandonment fears often have atypical features of depression, cluster B personality traits (e.g., borderline personality disorder), somatic disorders (i.e., physical problems not explained by known medical causes), and obsessive-compulsive tendencies (eating disorders, perfectionistic traits, etc.).

Typical reactions that therapists or others may have include feelings of helplessness, anger, guilt, frustration, "walking on eggshells", feeling inadequate, and an impulse toward boundary crossing. This highlights the importance of maintain healthy boundaries.

Tips for supporting someone with abandonment issues

OPEN AND HONEST COMMUNICATION

Secrets don’t go over well when you’re dealing with someone who has abandonment issues. Someone who fears abandonment usually has trouble trusting people. If they’re unsure of the way you feel, they may assume that you want to leave them, and they might take off or sabotage the relationship before you have a chance to hurt them.

Therefore, it helps if you’re clear and direct about how you feel. Setting up open communication from the beginning will allow you to create a connection that’s based on honesty instead of the insecurity that plagues people with abandonment issues.

DON'T ENGAGE IN THE CONTENT OF ARGUMENTS

Because someone with fear of abandonment may have so many false beliefs about their worth and their roles at work, in a family, or in relationships, they may try to manipulate you when you’re having an intense discussion or argument.

Someone with abandonment issues often wants to know that they’re not going to be left behind. They may try to sway the conversation so that you’re constantly affirming and comforting them.

For example, they may say things like, “I know you don't care that much about me" or "I can tell you don't like coming to visit me." They don’t do this on purpose. It’s a reflex that they’ve learned from experience.

If they can get continual engagement from you, they don’t feel the abandonment. The problem is that if you play into these games, the moment you stop engaging, they experience abandonment again. The best way to deal with abandonment issues is to state clearly that you’re ready to listen ONLY when they are ready to say what they’re really feeling and thinking. Doing this prevents you from continually goading them to get them to express themselves and shows them that they’re important to you even if you’re not giving them constant attention.

VALIDATE FEELINGS, NOT THE CONTENT

Avoid telling someone with fear of abandonment that they’re wrong. Instead, validate their feelings before trying to get them to see things from a different perspective. Most of the time, when they feel seen and understood, their fight or flight response diminishes, and their reasoning mind can become more engaged.

Common accusation: "You don't give a shit about me. It's your birthday and all you care about is yourself! I'm struggling and need help!"

Common response from a well-intentioned loved one: "I do care about you. I didn't know you were struggling like this..." blah blah blah explaining and rationalizing what you are doing in an attempt to reassure them.

What the person fearing abandonment hears: "Your feelings don't matter. See how this explanation justifies and proves that your reaction is selfish and ridiculous?"

Better response: "It sounds like you're having a really difficult time and that you don't feel heard or understood. I can see how attending my birthday may feel like I am leaving you behind. It hurts my feelings to see you this way."

The worst thing a person could do is react by trying to gain power and authority through splitting or telling the person that others wouldn't agree with them (common reaction). "I'm going to see what others think about this." Or even worse "You're so selfish and entitled. Grow up!"

DON'T TAKE THINGS PERSONALLY

People with abandonment issues may act withdrawn or jealous. This could make you feel as though you’re doing something to hurt them. They may even try to blame you outright. But people with abandonment issues aren’t reacting to anything that you did. They are following patterns that were established when they experienced their trauma. They’re remembering what it felt like to be hurt, and they’re trying to avoid getting in that situation again.

After they blow up or act irrationally, people with abandonment issues will often feel ashamed of their behavior. That’s a great time to talk about it and reassure them that you’re there for them when they’re experiencing those intense emotions.

DON'T ENABLE UNHEALTHY BEHAVIORS

If you allow someone you care about to engage in the unhealthy behaviors that they’re used to (such as manipulation, blame, and isolation) you reinforce their abandonment issues. Setting your own boundaries makes it easier for them to learn to respect themselves. Being independent and firm in what you need from the relationship will make it more difficult for them to cling to you out of codependency. This is easier said than done.

When you care about someone, you want to coddle and comfort them. But that constant input bolsters their abandonment issues. They feel good when they’re getting your attention, but they disintegrate when you’re off doing your own thing, and the cycle repeats. Standing your ground and knowing what you want from the relationship will help you ask for what you want without hurting them. It also sets a good example. They can learn to set boundaries and be independent, too.

UNDERSTAND WHY THEY DO WHAT THEY DO

When you’re dealing with someone who has abandonment issues, one of the hardest things to deal with is their instinct to sabotage the relationship. Someone with abandonment issues is so afraid of being rejected that they often damage the connection on purpose. They don’t want to be alone, but it’s better to be rejected for a reason than to be left just because they’re not good enough.

If they exhibit negative behavior or damage the relationship, the people they care about have a reason to leave. If those people do abandon them, at least it’s for a reason and not just a reflection of the individual’s worth. Because of this, people with abandonment issues may pull away from you for no reason. They may try to pick fights. If they abandon you first, they’ll avoid the pain of being abandoned. Be prepared to prove yourself. You’ll need to consistently show them that even though other people have hurt them in the past, you aren’t going to.

YOU DO NOT NEED TO FIX THEM

You are not responsible for fixing a loved one's abandonment issues. Don’t make promises that you can’t keep--you never know what the future holds. You can promise that you will always do your best to listen, but someone with abandonment issues believes that everyone will eventually leave them. They may never believe you no matter how many promises you make. In fact, making promises might drive them away. When they have a high expectation of a secure future, there’s more to lose.

SETTING AN EXAMPLE

You don’t have to engage with, or work with, someone who has abandonment issues. But if you care about them and want to make the relationship work, it helps to understand where they’re coming from. Remind them why you love them, but don’t indulge or overprotect them. By setting your own boundaries and living your life, you’ll show them that they can do the same.

This post was reviewed by a licensed mental health professional.

Understanding Attachment Styles

Understanding Attachment Styles: A Guide to Building Healthier Relationships

Have you ever wondered why some relationships flow effortlessly while others feel like a constant tug-of-war? The answer might lie in your attachment style. Developed during childhood, attachment styles are the patterns of behavior and thinking we bring into our relationships. These styles influence how we connect with others, communicate our needs, and respond to challenges.

There are four main attachment styles: secure, anxious, avoidant, and disorganized. Understanding your attachment style (and those of your loved ones) can be a game-changer for your personal growth and relationships.

1. Secure Attachment: The Ideal Balance

What it looks like: People with a secure attachment style feel comfortable with intimacy and independence. They trust their partners and themselves, communicate effectively, and are emotionally available.

How it develops: Secure attachment forms when caregivers are consistently responsive, nurturing, and supportive. As children, these individuals learn that relationships are safe, and their needs will be met.

In relationships: They’re comfortable with emotional closeness but also respect their partner’s autonomy. They tend to handle conflicts constructively and maintain a positive outlook on relationships.

Signs you may have a secure attachment:

You trust your partner and feel trusted in return.

You’re not overly anxious about being abandoned or smothered.

You communicate openly and effectively.

2. Anxious Attachment: Fear of Abandonment

What it looks like: People with an anxious attachment style crave closeness but fear rejection. They may need frequent reassurance and can become overly preoccupied with their relationships.

How it develops: This style often stems from inconsistent caregiving during childhood. A caregiver who was sometimes nurturing and other times unavailable can lead to uncertainty about love and attention.

In relationships: They may come across as clingy or overly dependent, constantly seeking validation from their partner. Small changes in the partner’s behavior can trigger intense feelings of insecurity.

Signs you may have an anxious attachment:

You worry your partner doesn’t love you as much as you love them.

You feel anxious or abandoned when they’re not immediately available.

You seek constant reassurance or fear conflict will lead to a breakup.

3. Avoidant Attachment: Fear of Intimacy

What it looks like: People with an avoidant attachment style value independence to the extent that they may avoid emotional closeness. They may appear distant, self-reliant, or emotionally unavailable.

How it develops: Avoidant attachment often arises from caregivers who were dismissive, neglectful, or overly focused on fostering independence, leading the child to suppress their need for closeness.

In relationships: They often keep their partners at arm’s length and may struggle to express emotions. They may interpret intimacy as a threat to their independence.

Signs you may have an avoidant attachment:

You feel uncomfortable with emotional closeness.

You prioritize independence over connection.

You may withdraw or shut down during conflict.

4. Disorganized Attachment: The Push-Pull Dynamic

What it looks like: People with a disorganized attachment style struggle with conflicting desires for closeness and fear of intimacy. They may oscillate between pursuing and avoiding connection.

How it develops: This style is often rooted in childhood trauma, neglect, or abuse. Caregivers who were both a source of comfort and fear can create a deep internal conflict.

In relationships: They may feel intense emotional highs and lows, struggle with trust, and exhibit unpredictable behavior. Their relationships can feel chaotic or unstable.

Signs you may have a disorganized attachment:

You crave intimacy but also fear being hurt or rejected.

You feel conflicted or overwhelmed by relationships.

You may act inconsistently, pushing partners away while longing for closeness.

How to Use This Knowledge

Your attachment style is not a life sentence. While it’s deeply rooted in early experiences, it’s possible to develop healthier patterns. Here are some tips to move toward more secure attachment:

Awareness is key: Recognize your attachment style and how it affects your relationships.

Practice self-regulation: Learn to manage emotional triggers and anxieties.

Communicate openly: Express your needs and fears with trusted loved ones.

Seek support: Therapy, especially approaches like attachment-based therapy, can help you rewrite old patterns.

Build secure connections: Surround yourself with people who are consistent, supportive, and emotionally available.

Understanding attachment styles can shine a light on the hidden dynamics of your relationships. Whether you’re secure, anxious, avoidant, or disorganized, the goal isn’t perfection—it’s growth. By becoming aware of your patterns and making intentional changes, you can create healthier, more fulfilling connections.

So, which attachment style do you resonate with most?

This post was reviewed by a licensed mental health professional.

How to Choose the Right Mental Health Provider: A Comprehensive Guide

Seeking help for mental health is a brave and essential step toward well-being. However, with so many different types of mental health providers available, it can be overwhelming to figure out where to start. Whether you're dealing with anxiety, depression, relationship issues, or any other psychological concern, finding the right professional to guide you on your journey is crucial. Here’s a comprehensive guide to help you make an informed decision about choosing the right mental health provider for you.

1. Understand Your Needs

The first step in choosing a mental health provider is identifying what you need help with. Are you looking for short-term support during a stressful period, or do you need ongoing treatment for a chronic mental health condition? The type of mental health issue you're dealing with will influence the kind of professional you should seek.

Therapy for specific problems: For issues like stress, anxiety, or relationship problems, a therapist or counselor may be a good fit.

Medication for mental health conditions: If you have a condition like depression, bipolar disorder, or ADHD that may require medication, you'll want to see a psychiatrist, psychiatric nurse practitioner, or a primary care physician with experience in mental health.

Specialized treatments: If you’re dealing with trauma, OCD, or eating disorders, seek out a provider who specializes in evidence-based therapies like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure and response prevention (ERP), or trauma-focused therapy.

2. Know the Types of Mental Health Providers

Not all mental health professionals provide the same services. Here’s a quick breakdown of the common types of providers and what they can offer:

Psychiatrists: Medical doctors who specialize in diagnosing and treating mental health disorders. They can prescribe medication and may provide therapy.

Psychologists: Trained in clinical psychology, they can diagnose mental health conditions and provide therapy but typically cannot prescribe medication (except in certain states).

Licensed Clinical Social Workers (LCSWs): Focus on providing therapy and connecting clients with community resources, often specializing in helping clients manage daily life stressors.

Marriage and Family Therapists (MFTs): Specialize in relationship issues, including family dynamics, couple’s therapy, and parenting support.

Licensed Professional Counselors (LPCs): Provide therapy for a range of issues like anxiety, depression, and grief, typically focusing on short-term problem-solving.

Nurse Practitioners: Some nurse practitioners (with a focus on psychiatry) can prescribe medications and provide mental health care, often working in collaboration with other professionals.

3. Consider the Provider’s Approach

Therapists and mental health professionals often have different approaches and philosophies regarding treatment. Some common therapeutic modalities include:

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Focuses on changing negative thought patterns and behaviors.

Psychodynamic Therapy: Explores unconscious patterns stemming from early childhood experiences.

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT): Teaches coping strategies for managing intense emotions, particularly useful for borderline personality disorder and other emotional regulation issues.

Humanistic Therapy: Focuses on self-actualization and personal growth.

Mindfulness-based Approaches: Integrate mindfulness practices to reduce stress and increase emotional awareness.

It’s important to find a provider whose treatment approach resonates with you. Many therapists integrate several approaches, and you can ask about their preferred methods during an initial consultation.

4. Check Credentials and Experience

When you’re entrusting someone with your mental health, it’s important to ensure they are licensed and have the proper qualifications. Look for professionals who have:

Relevant degrees (e.g., MD, PhD, PsyD, MSW, etc.).

State licensure, which ensures they’ve met the legal and ethical standards to practice.

Experience working with issues similar to yours. For example, if you're seeking help for trauma, look for a therapist trained in trauma-informed care.

It can also be helpful to ask for recommendations from your primary care provider or friends who have had positive experiences.

5. Think About Accessibility and Affordability

Practical considerations like location, availability, and cost play a significant role in choosing a mental health provider. Here are a few key factors:

Insurance Coverage: Check whether the provider accepts your insurance. If you're paying out-of-pocket, ask about fees and whether they offer sliding-scale rates based on income.

Location: Are they close enough to you for regular appointments? If you’re open to virtual therapy, many providers now offer telehealth services, which can expand your options.

Availability: Can they see you at times that work with your schedule? If you’re in need of immediate help, look for a provider with availability sooner rather than later.

6. Trust Your Instincts

The relationship between you and your mental health provider is key to the success of your treatment. It’s essential that you feel comfortable and understood. During your first meeting, ask yourself:

Do I feel heard and respected by this provider?

Does the provider seem knowledgeable about my issues?

Am I comfortable discussing personal thoughts and feelings with this person?

If you don’t feel a connection or comfort level after a few sessions, it’s okay to consider switching providers. Finding the right fit may take time, but it’s important for your long-term mental health.

7. Ask for a Consultation

Many mental health providers offer a free or low-cost initial consultation, either over the phone or in person. This can be an opportunity to ask about their approach, experience, and how they might work with you on your specific issues. Don’t hesitate to ask questions—this is a two-way street, and you should feel empowered to choose the best provider for your needs.

Final Thoughts

Finding the right mental health provider can feel daunting, but it’s a crucial step toward improving your emotional well-being. By understanding your needs, exploring different types of providers, considering their approaches, and trusting your instincts, you’ll be better equipped to choose someone who can help you navigate your mental health journey.

Taking that first step is the hardest, but with the right support, the path forward will become much clearer.

This post was reviewed by a licensed medical provider.

Tips for Working with a Narcissist

Navigating a professional environment with a narcissistic boss or coworker can be challenging. People with narcissistic traits often display behaviors such as arrogance, entitlement, lack of empathy, and a constant need for admiration or validation. Here are some useful strategies and tips to help you manage these dynamics effectively:

1. Manage Expectations

Understand their Traits: Recognize that narcissists may prioritize their own needs, ideas, and success over others. They may not provide the acknowledgment or support you hope for, and they might not be open to constructive criticism.

Limit Emotional Investment: Maintain realistic expectations about their behavior. Avoid seeking validation or emotional support from them, as their responses may be unpredictable or self-centered.

2. Maintain Professionalism

Stay Calm and Composed: Keep your emotions in check during interactions, especially in stressful situations. Narcissists may try to provoke or manipulate your emotions to assert control or dominance.

Use Neutral Language: Communicate in a calm, direct, and factual manner. Avoid emotional or overly subjective language, which they may perceive as a challenge or an opportunity to manipulate.

3. Set Boundaries

Be Clear and Firm: Clearly define what you will and will not tolerate in terms of behavior and interaction. Narcissists may test boundaries, so consistency is key.

Know When to Say No: Politely but firmly decline unreasonable requests or tasks that fall outside of your role or capacity. Offer alternative solutions when appropriate.

4. Stay Focused on Your Goals

Prioritize Your Work: Focus on your responsibilities and professional goals. Don’t get distracted by drama or conflicts they may create.

Document Interactions: Keep records of communications, requests, and decisions. This can be helpful if conflicts arise or if you need to protect yourself against manipulation or blame.

5. Learn to Manage Up

Understand Their Motivations: Identify what drives your narcissistic boss or coworker. They often crave admiration, control, and recognition. Use this to your advantage by framing your ideas in a way that aligns with their goals.

Give Constructive Praise: Narcissists often respond well to flattery. Offering genuine, specific praise can help you build rapport and make them more receptive to your ideas or feedback.

6. Protect Your Well-being

Avoid Personalization: Remember that their behavior reflects their issues, not your worth or abilities. Don’t internalize their criticism or negativity.

Seek Support: Talk to trusted colleagues, mentors, or a therapist to help you process your experiences and maintain your mental health. Having a supportive network can help you manage the stress associated with these dynamics.

7. Know When to Escalate or Exit

Escalate Concerns Appropriately: If their behavior crosses into harassment or abuse, document the instances and escalate the issue through appropriate channels, such as HR or a supervisor.

Consider Moving On: If the environment becomes too toxic or damaging, consider looking for opportunities elsewhere. No job is worth sacrificing your mental health or well-being.

8. Stay Detached and Objective

Avoid Getting Drawn into Drama: Narcissists may create conflicts or dramatic situations to assert control or maintain attention. Remain objective and avoid getting sucked into unnecessary drama.

Keep Interactions Brief and to the Point: Limit the length and depth of your interactions when possible. Focus on the facts and the tasks at hand.

9. Cultivate Emotional Intelligence

Practice Empathy with Detachment: While it may seem counterintuitive, understanding that narcissistic behavior often stems from deep insecurities can help you depersonalize their actions. However, maintain emotional detachment to protect yourself.

Use Active Listening Techniques: Acknowledge their perspective without agreeing or engaging in arguments. This can help diffuse potential conflicts and maintain a more neutral environment.

10. Use Strategic Communication Techniques

Mirror Their Language: Use phrases and terminology that resonate with them. For example, if they frequently speak about "winning," frame your ideas in terms of "success" or "achieving goals."

Ask Leading Questions: Guide them toward your desired outcome by asking questions that make them feel like the idea or decision is theirs.

By applying these strategies, you can better manage your interactions with a narcissistic boss or coworker and minimize the negative impact on your professional life. Remember to prioritize your well-being and know when it's time to set firm boundaries or seek other opportunities.

This content was reviewed by a licensed medical professional.

An Introduction to Pain

Introduction to Pain

Pain has been defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as

“An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage."

Below are some definitions to review.

Pain is the number one reason patients present to physicians. 19% of adults in the United States report persistent pain (defined as constant or frequent pain lasting for at least 3 months).

In a 2014 study by Kennedy et al, rates of persistent pain were highest for

Women

Adults ages 60–69 years

Adults who rated their health as fair to poor

Adults who were overweight or obese

Adults who were hospitalized one or more times in the preceding year.

The Physiology of Pain

Nociceptors

Pains signals are detected by sensory neurons called nociceptors. Nociceptors, also called pain fibers, are neurons that detect damage to tissues and then transmit pain signals to the spinal cord. Different nociceptors detect different types of painful stimuli.

Nociceptors may be myelinated (their axons are insulated by a myelin sheath) or unmyelinated (no myelin sheath around the axon). Recall that myelination increases the conduction velocity, or speed, of signals (i.e., action potentials) as they travel to their destination.

The different types of nociceptors (i.e., pain fibers) are illustrated below.

A-delta Types I and II (myelinated) fibers rapidly transmit signals for "sharp" pain to the spinal cord.

C fibers (unmyelinated) fibers slowly transmit signals for "dull" pain to the spinal cord. C fibers have been implicated in chronic pain.

Nociceptors have free nerve endings (unlike receptors for touch/vibration which have corpuscles) and respond to a range of physical and chemical stimuli.

Normally, nociceptors only respond to signals capable of causing damage. If these receptors become hypersensitive, pain signals can be transmitted even in the absence of tissue damage.

Another type of sensory neuron, called A-Beta fibers, transmit non-noxious mechanical stimuli such as light touch, pressure, and vibration signals to the spinal cord. These fibers are myelinated, so the signal travels fast.

How do Pain Signals Travel to the Brain?

Have you ever stubbed your toe? Immediately after stubbing your toe, your reflexes kick in and you immediately withdraw your foot.

The immediate pain you feel is from the A-delta fibers. Within milliseconds, the dull pain sets in and you REALLY feel it. The delay occurs because C-fibers travel slower than the A-delta fibers.

See the diagram below, which illustrates the fast and slow responses of A-delta and C fibers, respectively.

Tissue damage releases many signaling molecules

After an injury, numerous proteins and signaling molecules are released that immediately initiate the inflammatory process and wound healing process. The substances released from damaged tissues that activate nociceptors are tabulated below.

After a traumatic injury, immune cells and damaged tissue release bradykinins, prostaglandins, potassium, substance P, and histamine which activate nociceptors. Nociceptors have their cell bodies within the dorsal root ganglion and send pain signals to the spinal cord. Because the signals are sent TO the spinal cord/brain, we call them afferent signals (NOTE: signals are called efferent when they are sent from the brain/spinal cord TO the periphery).

After synapsing in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, the signal is modulated and then sent up the spinal cord to the brain through the anterolateral (i.e., spinothalamic) pathway for further processing.

Pain Modulation in the Spinal Cord: Opioids, Serotonin, and Norepinephrine

The modulation of pain signals occurs in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Recall that pain signals are sent from the periphery to the spinal cord via nociceptors. These nociceptors synapse onto other neurons within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

Once the pain signals reach the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, the signals are altered and modified by other neurons. These other neurons originate from various areas. Some of them originate from the brainstem and travel down to synapse on, and modify, pain signals.

These descending fibers from the brain stem may be serotonin neurons, norepinephrine neurons, or opioid-producing neurons.

These descending fibers dampen or decrease the intensity of the pain signals before they travel up to the brain. This is why we use serotonin-norepinephrine medications such as duloxetine (Cymbalta) and nortriptyline (Pamelor) for pain management.

There are also nerve fibers, called mechanoreceptors, that originate outside the spinal cord and carry non-painful mechanical signals such as vibration, soft touch, and pressure from muscles and skin. These mechanoreceptors, which are also called A-Beta fibers, also synapse on neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord where they decrease or dampen pain signals. This is why we rub our wounds!

As we've discussed, there are a number of neurons (e.g., mechanoreceptors, serotonin neurons, and norepinephrine neurons) that diminish pain signals in the spinal cord. Opioid-producing neurons are another type of neuron that diminish pain signals.

Endogenous opioids are opioids produced naturally by our bodies. Endogenous opioids play a role in dampening the pain signals in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. This is why we use opioid medications (e.g., hydrocodone, morphine, fentanyl) for pain management.

See the figures below

The Gate Theory of Pain

As described above, pain signals transmitted by C-fibers (red neuron in the diagrams below) and non-pain signals transmitted by A-Beta fibers (yellow neuron in the diagrams below) arrive at the spinal cord and make a pit stop in the dorsal horn by synapsing on both inhibitory interneurons (red neuron in the diagrams below) and neurons destined for the brain (pink in the diagrams below).

C-fibers and A-beta fibers (i.e., mechanoreceptors) act in opposite ways.

The C-fibers (red neurons in the diagrams below) inhibit the inhibitory interneuron and stimulate the neuron transmitting the pain signal (pink in the diagram below). By inhibiting the inhibitory interneuron, the pain signal is enhanced.

A-beta fibers, which are mechanoreceptors, do the opposite of C-fibers. A-beta fibers (yellow neuron in the diagram below) synapse on inhibitory interneurons (red neuron in the diagram below) and stimulate them. By stimulating the inhibitory interneurons, the pain signal is reduced.

This is why we have a tendency to rub our wounds immediately after we suffer an injury. By rubbing the wound, we dampen the pain signal.

As you can see, the dorsal horn acts like a checkpoint where these pain signals can be modified before traveling up the spinal cord to the brain. We call this the "Gate Theory" of pain. The dorsal horn acts as a "gate" for pain signals.

Perception of Pain

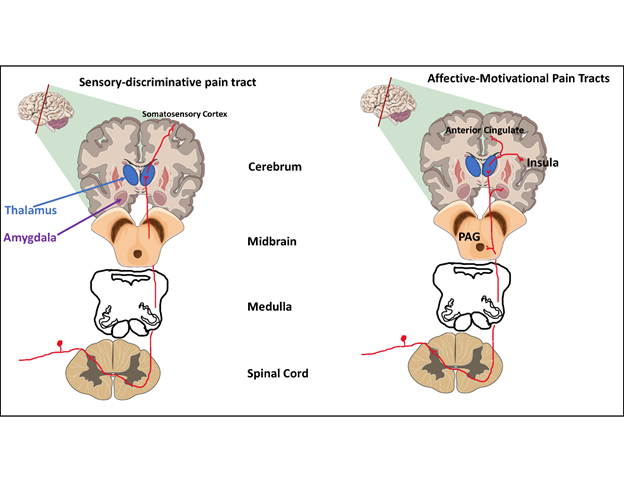

Two separate but parallel pathways send two different types of information.

The Sensory-discriminative pathway sends information about the location of the pain.

The Affective-motivational pathway sends information about the intensity of the pain.

The integration of these two pathways (and others which are not mentioned here) result in the perception of pain. Obviously, this is a very simplified explanation and there is much more complexity, but it gives the learner a basic understanding of how we perceive pain.

Sensory-discriminative

Where does it hurt?

Spinothalamic tract (traditional pain pathway)

Nerve fibers from the Sensory-discriminative tract (spinothalamic tract) are located in the anterolateral region of the spinal cord and synapse in the thalamus. From the thalamus, nerve fibers make their way to the somatosensory cortex where pain is first detected or perceived.

Affective-motivational

How much does it hurt?

Spinoreticular tract

Spinomesencephalic tract

Nerve fibers from the affective motivational tracts are also located in the anterolateral region of the spinal cord and synapse on the reticular formation, periaqueductal gray, amygdala, and medial thalamus.

From there, information is then sent to the "emotional centers" in the cerebral cortex such as the anterior cingulate cortex, insular cortex, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala where pain signals are integrated into an experience.

Brain Regions Involved in Processing Pain Signals: Thalamus, Anterior Cingulate Cortex, Prefrontal Cortex, and Insular Cortex

Pain Tolerance

Pain tolerance occurs on a spectrum. Brain imaging studies have demonstrated that subjects with less pain tolerance have greater activation of the cortical areas discussed previously including the Anterior Cingulate Cortex, Insular cortex, Prefrontal Cortex, and Somatosensory Cortex).

Genetics also plays a role.

Variants of the gene for Catechol-o-methyl transferase (COMT), an enzyme that breaks down catecholamine neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine and dopamine, have been associated with different pain tolerances. Interestingly, individuals with schizophrenia may have a higher tolerance for pain which is supported by the variations in the gene for Catechol-o-methyl transferase (COMT).

References

Arciniegas, Yudisorderfsky, Hales (editors). The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook Of Neuropsychiatry And Clinical Neurosciences. Sixth Edition.

Bear, Mark F.,, Barry W. Connors, and Michael A. Paradiso. Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain. Fourth edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2016.

Blumenfeld, Hal. Neuroanatomy Through Clinical Cases. 2nd ed. Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates, 2010.

Cooper, J. R., Bloom, F. E., & Roth, R. H. (2003). The biochemical basis of neuropharmacology (8th ed.). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

Higgins, E. S., & George, M. S. (2019). The neuroscience of clinical psychiatry: the pathophysiology of behavior and mental illness. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer.

Iversen, L. L., Iversen, S. D., Bloom, F. E., & Roth, R. H. (2009). Introduction to neuropsychopharmacology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Levenson, J. L. (2019). The American Psychiatric Association Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine and consultation-liaison psychiatry. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Mendez, M. F., Clark, D. L., Boutros, N. N. (2018). The Brain and Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Neuroanatomy. United States: Cambridge University Press.

Schatzberg, A. F., & DeBattista, C. (2015). Manual of clinical psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Schatzberg, A. F., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2017). The American Psychiatric Association Publishing textbook of psychopharmacology. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Neuroscience, Sixth Edition. Dale Purves, George J. Augustine, David Fitzpatrick, William C. Hall, Anthony-Samuel LaMantia, Richard D. Mooney, Michael L. Platt, and Leonard E. White. Oxford University Press. 2018.

Stahl, S. M. (2013). Stahl's essential psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific basis and practical applications (4th ed.). New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press.

Stern, T. A., Freudenreich, O., Fricchione, G., Rosenbaum, J. F., & Smith, F. A. (2018). Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry. Edinburgh: Elsevier.

Whalen, K., Finkel, R., & Panavelil, T. A. (2015). Lippincotts illustrated reviews: pharmacology. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer.

Hales et al. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. 6th Ed.

____

This article was reviewed by a licensed medical professional.

Fear, Anxiety, and Worry in the Brain

Fear, anxiety, and worry are complex emotional states that involve various processes in the brain and are crucial for survival. Let’s review how they are processed in the brain. Then, we will discuss how exposure therapies can help with fear, anxiety, and worrying.

FEAR

Fear is a response to imminent threat. It most often begins with a sensory stimulus, which could be a sight, sound, or other cue that signals potential danger. After the sight, sound, or other cue is processed by the sensory organs (e.g., eyes, ears), the signal is sent to a relay station in the brain called the thalamus, which then sends the signal to the amygdala.

The amygdala is a structure deep within the brain that assesses the emotional relevance of sensory stimuli. If the amygdala perceives the stimulus as a threat, it quickly activates a response by sending signals that initiate the body's fight-or-flight (or freeze) response (i.e., elevated heart rate, respiratory rate, sweating, vision changes).

Simultaneously, the thalamus also sends sensory signals to the brain’s cerebral cortex, the area responsible for higher-order thinking and evaluation. The cortex decides whether the perceived threat is real and modulates the amygdala's response accordingly (i.e., shuts it down/off).

The hippocampus, which is crucial for memory, is also activated which helps us remember the experience for the future. Unfortunately, as you will see, this also means the fear circuit can be triggered by experiences that remind you of the past threatening experience.

ANXIETY AND WORRYING

Unlike fear, which is a response to a specific and present threat, anxiety and worrying involve the anticipation of future threats. Anxiety is more a feeling/emotion whereas worry is more a cognitive process characterized by repetitive, uncontrollable thoughts about potential negative future events.

The amygdala, as described above, also plays a role in both anxiety and worrying. People with anxiety often have an overly sensitive amygdala which means they are more likely to perceive neutral or uncertain situations as threatening.

The cerebral cortex, which is involved in planning, decision-making, foresight, and attention, has direct connections with the amygdala and assesses and sometimes overestimates the danger or negative outcomes of future events. This is because the cerebral cortex may be unable to shut down the heightened responses from the amygdala, which leads to chronic anxiety and worrying.

Finally, the hippocampus is responsible for storing emotional memories for the future. Unfortunately, this means the neural circuits for fear, anxiety, and worry can be triggered by experiences that remind you of the past threatening experience.

NEUROTRANSMITTERS (BRAIN CHEMICALS)

Neurotransmitters (brain chemicals) like serotonin, norepinephrine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are important in regulating the circuits described above. These brain chemicals alter the activity of the circuits and can increase or decrease anxiety and worrying. This is why medications that alter serotonin (e.g., Prozac, Zoloft, Lexapro), Norepinephrine (e.g., Cymbalta, Effexor, Prazosin), and GABA (Xanax, Valium, Ativan, Klonopin) signaling are helpful for people with anxiety.

SUMMARY OF FEAR, ANXIETY, AND WORRY IN THE BRAIN

Thalamus: A relay station in the brain for sensory and motor signals.

Amygdala: This is the brain's fear center. It's responsible for detecting threats and initiating the body's fight-or-flight response. In people with anxiety disorders, the amygdala may be hyperactive or overly sensitive.

Cerebral Cortex: These regions have direct connections with the amygdala and are important in regulating emotions and exerting control over the amygdala's fear responses. The cerebral cortex is involved in higher-order functions like attention, planning, decision-making, and moderating social behavior. It's also crucial for regulating emotions and exerting control over the amygdala's fear responses.

Hippocampus: This area plays a key role in forming and retrieving memories, including those that elicit fear or anxiety.

VIDEO: Neurobiology of Anxiety and Worry

___ This post was reviewed by a licensed medical professional.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a form of psychotherapy developed by Francine Shapiro in the late 1980s. It is primarily used to treat individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The therapy's unique aspect involves bilateral sensory input, such as side-to-side eye movements, hand tapping, or auditory tones. Here's a detailed overview of its methodology, how it works, and the theories supporting it.

OVERVIEW OF EMDR

Phases of Treatment

EMDR is structured into eight distinct phases focusing on past, present, and future aspects of a traumatic memory. The phases include history taking, preparation, assessment, desensitization, installation, body scan, closure, and reevaluation.

Targeting Memories

In EMDR, the therapist and client identify specific traumatic memories to target. These include the main event and any related incidents that contribute to the distress.

Bilateral Stimulation

This is the most distinctive element of EMDR. The therapist guides the client in lateral eye movements, or other bilateral sensory input, while the client recalls the traumatic memory. The purpose is to reduce the vividness and emotion associated with the memories.

HOW EMDR WORKS

Desensitization

The client focuses on the trauma memory while engaging in bilateral stimulation. This process is believed to desensitize the person to the emotional impact of the memory.

Reprocessing

The goal is to reprocess the traumatic memory so that it is integrated into a coherent narrative of the past. The distress is reduced, and the memory is associated with more adaptive beliefs and feelings.

Installation

Positive beliefs are reinforced and "installed" to replace the negative emotions and beliefs associated with the traumatic memories.

Body Scan

After the reprocessing phases, clients are asked to notice any residual somatic sensations. Further bilateral stimulation may be used to alleviate any remaining tension.

THEORIES SUPPORTING EMDR

Adaptive Information Processing (AIP) Model

This is the primary theoretical model for EMDR. It suggests that psychological distress is due to unprocessed memories. EMDR facilitates the accessing and processing of traumatic memories to bring them to an adaptive resolution.

Neural Mechanisms

Some researchers propose that the bilateral stimulation in EMDR may mimic the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) phase of sleep, which is involved in processing emotional memories. This stimulation may help facilitate the connection between the brain's memory and emotion networks, aiding in the processing of traumatic memories.

Psychological Theories

Various psychological theories have been used to explain the efficacy of EMDR, including Pavlovian conditioning, whereby the distressing memory is "extinguished" through repeated exposure while the individual is in a different emotional state.

CONCLUSIONS

Numerous studies have shown EMDR to be effective in treating PTSD and other trauma-related disorders. It is recognized as an effective treatment by organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association and the World Health Organization. In summary, EMDR is a complex, multi-phased therapy designed to alleviate the distress associated with traumatic memories. Its unique approach of bilateral stimulation, combined with traditional psychotherapeutic techniques, has made it a popular and effective treatment for trauma and PTSD. Despite some criticisms, its recognition by major health organizations underscores its value as a therapeutic tool. As with any therapy, its effectiveness can vary from person to person, and it's always recommended to work with a trained and experienced therapist.

___

This post was reviewed by a licensed medical professional.

Exposure Therapy

Exposure therapy is a psychological treatment designed to help you confront and diminish fear and anxiety. From a neurobiological perspective, exposure therapy facilitates changes in the brain that help reduce the symptoms of anxiety and fear.

MECHANISMS OF EXPOSURE THERAPY

Habituation

Repeated exposure to a feared object or context without any negative consequences can lead to habituation, where your body’s physical and emotional responses to fear decrease over time.

Extinction

Exposure therapy facilitates the creation of new memories that compete with the old fear memories. These new memories help tell your brain that fear-provoking situations are no longer dangerous. This process is known as extinction.

Inhibition

The cerebral cortex (i.e., your reasoning brain) helps to reduce your body’s fear response (i.e., your emotional brain). Over time, your reasoning brain gets better at inhibiting your emotional brain even when fear-provoking situations are encountered.

Emotional Processing

You learn to re-evaluate and change the meaning associated with the fear-provoking situation.

NEUROPLASTICITY AND EXPOSURE THERAPY

Strengthening New Pathways

With repeated exposure and new learning, your brain's neural pathways are altered – a process known as neuroplasticity. Connections between your cerebral cortex and your amygdala are strengthened, enhancing your brain's ability to control fear responses.

Reducing Reactivity

Over time, exposure therapy can reduce the hyper-reactivity of your amygdala, leading to decreased anxiety and fear responses.

LONG-TERM CHANGES

Reduced Sensitivity

Your amygdala becomes less sensitive to the triggers that once caused significant fear or anxiety.

Enhanced Regulation

There's an increase in the regulatory influence of your cerebral cortex over your amygdala, leading to better control over emotions and responses to fear.

Memory Reconsolidation

Each time a memory is recalled, it's susceptible to change. Exposure therapy can help you modify traumatic or fear-inducing memories every time they're retrieved, making them less distressing.

SUPPORTING EVIDENCE

Brain imaging studies show reduced activity in the amygdala after successful exposure therapy.

In summary, exposure therapy helps you by harnessing the brain's capacity for learning and adaptation. It reduces the irrational fear response by altering the neural pathways associated with fear and anxiety, leading to lasting changes in how the brain processes and responds to fear. These changes not only decrease anxiety but also enhance your ability to manage fear in a more adaptive and healthy manner.

___

This post was reviewed by a licensed medical professional.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a form of psychotherapy developed by Francine Shapiro in the late 1980s. It is primarily used to treat individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The therapy's unique aspect involves bilateral sensory input, such as side-to-side eye movements, hand tapping, or auditory tones. Here's a detailed overview of its methodology, how it works, and the theories supporting it.

OVERVIEW OF EMDR

Phases of Treatment

EMDR is structured into eight distinct phases focusing on past, present, and future aspects of a traumatic memory. The phases include history taking, preparation, assessment, desensitization, installation, body scan, closure, and reevaluation.

Targeting Memories

In EMDR, the therapist and client identify specific traumatic memories to target. These include the main event and any related incidents that contribute to the distress.

Bilateral Stimulation

This is the most distinctive element of EMDR. The therapist guides the client in lateral eye movements, or other bilateral sensory input, while the client recalls the traumatic memory. The purpose is to reduce the vividness and emotion associated with the memories.

HOW EMDR WORKS

Desensitization

The client focuses on the trauma memory while engaging in bilateral stimulation. This process is believed to desensitize the person to the emotional impact of the memory.

Reprocessing

The goal is to reprocess the traumatic memory so that it is integrated into a coherent narrative of the past. The distress is reduced, and the memory is associated with more adaptive beliefs and feelings.

Installation

Positive beliefs are reinforced and "installed" to replace the negative emotions and beliefs associated with the traumatic memories.

Body Scan

After the reprocessing phases, clients are asked to notice any residual somatic sensations. Further bilateral stimulation may be used to alleviate any remaining tension.

THEORIES SUPPORTING EMDR

Adaptive Information Processing (AIP) Model

This is the primary theoretical model for EMDR. It suggests that psychological distress is due to unprocessed memories. EMDR facilitates the accessing and processing of traumatic memories to bring them to an adaptive resolution.

Neural Mechanisms

Some researchers propose that the bilateral stimulation in EMDR may mimic the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) phase of sleep, which is involved in processing emotional memories. This stimulation may help facilitate the connection between the brain's memory and emotion networks, aiding in the processing of traumatic memories.

Psychological Theories

Various psychological theories have been used to explain the efficacy of EMDR, including Pavlovian conditioning, whereby the distressing memory is "extinguished" through repeated exposure while the individual is in a different emotional state.

CONCLUSIONS

Numerous studies have shown EMDR to be effective in treating PTSD and other trauma-related disorders. It is recognized as an effective treatment by organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association and the World Health Organization. In summary, EMDR is a complex, multi-phased therapy designed to alleviate the distress associated with traumatic memories. Its unique approach of bilateral stimulation, combined with traditional psychotherapeutic techniques, has made it a popular and effective treatment for trauma and PTSD. Despite some criticisms, its recognition by major health organizations underscores its value as a therapeutic tool. As with any therapy, its effectiveness can vary from person to person, and it's always recommended to work with a trained and experienced therapist.

___

This post was reviewed by a licensed medical professional.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)