What is Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)?

By Michael T. Ingram, Jr., M.D.

Overview

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder in children but may also occur in adults. About two-thirds of children diagnosed with ADHD experience symptoms in adulthood.

ADHD can be understood as a disorder of signal-to-noise regulation within neural networks responsible for attention, motivation, and executive function. Rather than a simple “deficit” of attention, it reflects impaired filtering of extraneous stimuli and difficulty amplifying task-relevant signals.

Neurobiologically, this involves dysregulation of dopaminergic and noradrenergic transmission within the prefrontal cortex (PFC), striatum, and anterior cingulate cortex—regions integral to cognitive control, working memory, and reward-based learning.

In essence, ADHD is not about not knowing what to do, but about not consistently being able to do what one knows—a disconnect between intention and implementation.

What are common symptoms of ADHD?

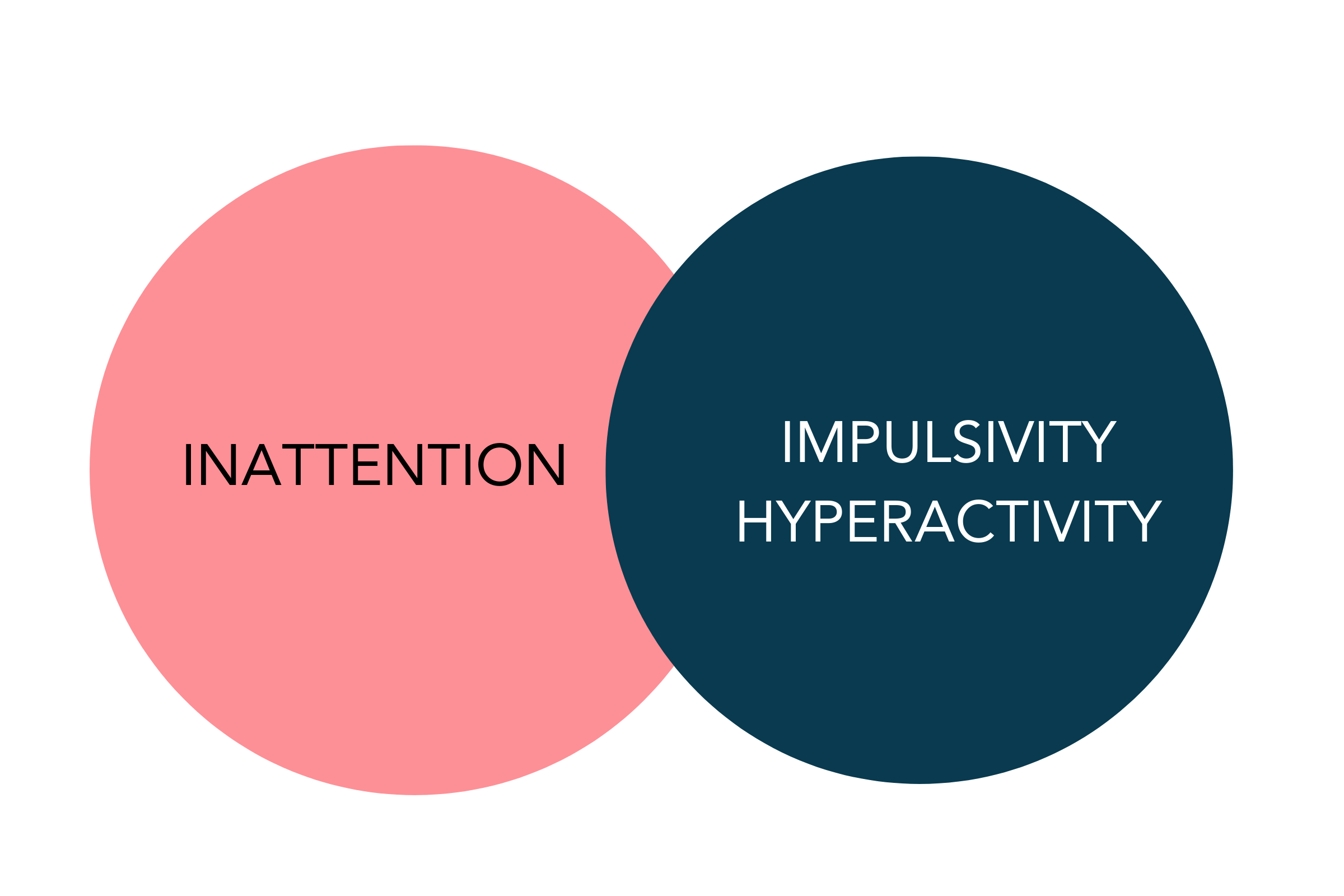

Symptoms of ADHD are organized into two major clusters:

Inattention: Forgetfulness, disorganization, difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play, frequent misplacing items, easily distracted, failure to finish tasks.

Hyperactivity/Impulsivity: Restlessness, difficulty remaining seated, incessant talking, fidgeting, impatience, blurting out answers, difficulty waiting one's turn, and interrupting or intruding on others.

Some individuals experience only inattentive symptoms or only hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms while others experience both (i.e., combined type).

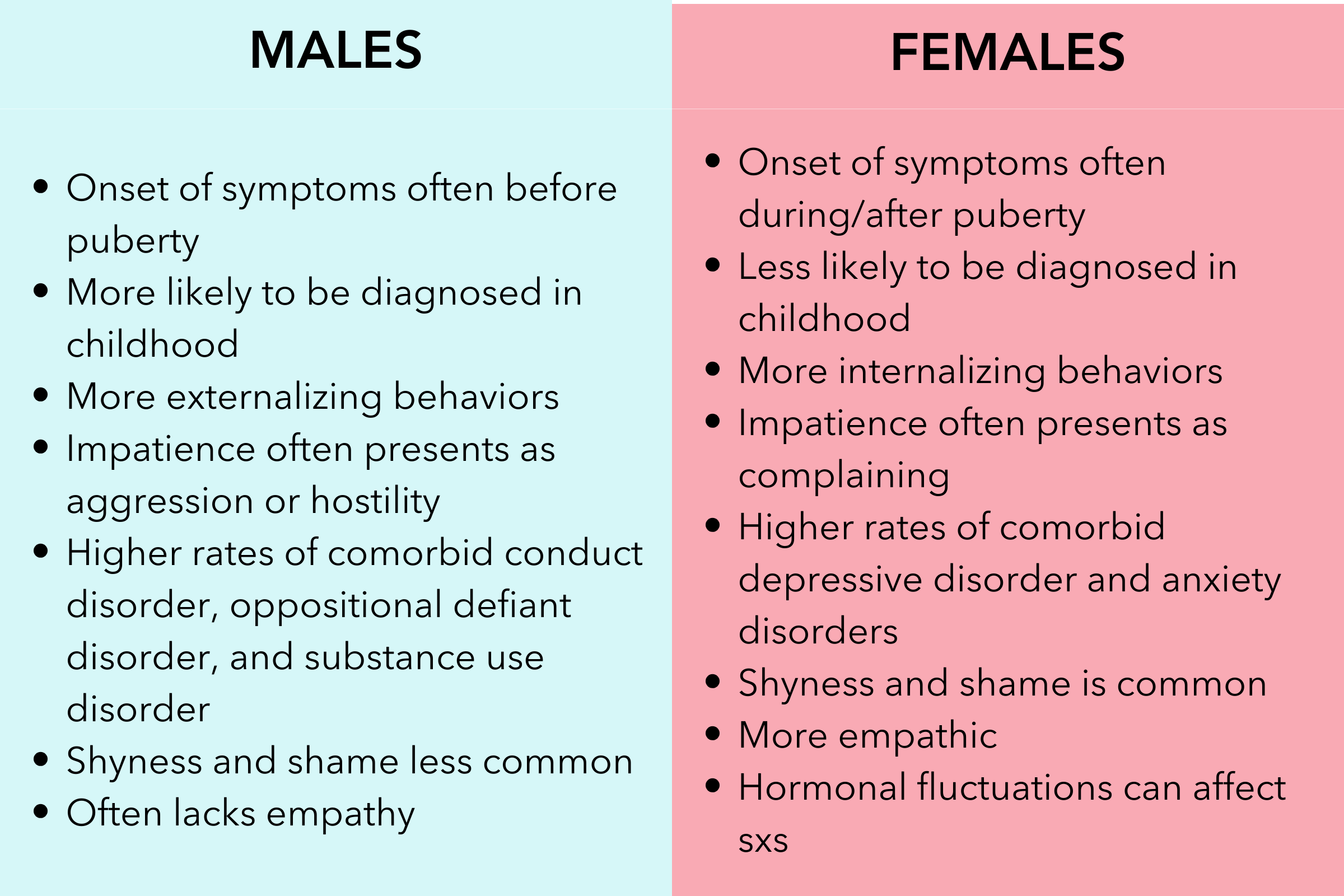

Males are more likely to be diagnosed in childhood or adolescence because males display more hyperactive symptoms than females and therefore are more likely to be referred for evaluation. Females usually experience more inattentive symptoms and, unfortunately, this means they are often not diagnosed until later in life.

How is ADHD Diagnosed?

The diagnosis of ADHD requires a comprehensive evaluation by a clinician experienced in ADHD. A comprehensive evaluation usually includes a combination of the following:

Clinical interviews.

Rating scales and questionnaires.

Review of past academic and work records.

Rule out other possible causes of symptoms.

Observations reported by family, friends, teachers, or employers.

DSM-5 CRITERIA

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is published by the American Psychiatric Association and is used by clinicians in the U.S. (and to some extent, globally) as a standard classification of mental disorders. It contains descriptions, symptoms, and other criteria necessary for diagnosing mental health disorders. Over the years, there have been several versions of the DSM, with the DSM-5-TR being the most recent edition published in 2022.

To be diagnosed with ADHD, an individual must meet the following criteria:

A. A persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development, as characterized by (1) and/or (2):

(1) Inattention: Six (or more) of the following symptoms have persisted for at least six months to a degree that is inconsistent with developmental level and that negatively impacts directly on social and academic/occupational activities:

Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes.

Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities.

Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly.

Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace.

Often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities.

Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort.

Often loses things necessary for tasks or activities.

Is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli.

Is often forgetful in daily activities.

(2) Hyperactivity and Impulsivity: Six (or more) of the following symptoms have persisted for at least six months to a degree that is inconsistent with developmental level and that negatively impacts directly on social and academic/occupational activities:

Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet or squirms in seat.

Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected.

Often runs or climbs in situations where it is inappropriate. (Note: In adolescents or adults, may be limited to feeling restless.)

Often unable to play or engage in leisure activities quietly.

Is often "on the go," acting as if "driven by a motor."

Often talks excessively.

Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed.

Often has difficulty waiting his or her turn.

Often interrupts or intrudes on others.

B. Several inattentive or hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms were present before age 12 years.

C. Several inattentive or hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms are present in two or more settings (e.g., at home, school, or work; with friends or relatives; in other activities).

D. There is clear evidence that the symptoms interfere with, or reduce the quality of, social, academic, or occupational functioning.

E. The symptoms do not occur exclusively during the course of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder and are not better explained by another mental disorder.

The DSM-5 also specifies the following subtypes of ADHD based on the predominant symptom pattern for the past six months:

Combined Presentation: If both Criteria A1 (Inattention) and A2 (Hyperactivity-Impulsivity) are met for the past six months.

Predominantly Inattentive Presentation: If Criterion A1 (Inattention) is met but Criterion A2 (Hyperactivity-Impulsivity) is not met for the past six months.

Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation: If Criterion A2 (Hyperactivity-Impulsivity) is met and Criterion A1 (Inattention) is not met for the past six months.

ADHD Symptoms in Adults

Inattention in adults often manifests as

Chronic boredom

Indecisiveness

Mind wandering/daydreaming

Procrastinating

Disorganization, forgetfulness, and poor task follow-through

Chronic lateness

Difficulty sustaining focus on tasks or conversations.

Easily distracted by external stimuli or internal thoughts.

Hyperactivity/Impulsivity in adults often manifests as

Inner restlessness or mental hyperactivity

Talkativeness

Excessive fidgeting

Engagement in high-risk activities

General impatience

Difficulty delaying gratification

Talking without thinking

Problems maintaining employment

Difficulty maintaining relationships

Attention seeking behavior

Self-medicating with drugs and alcohol

Multitasking

Chronic overcommitment (people pleasing, difficult time saying "no" to requests)

Chronic lateness, procrastination, and inconsistent productivity.

Difficulty prioritizing and completing tasks

Emotional dysregulation (frustration, rejection sensitivity)

Impulsive spending, speech, or interpersonal decisions.

In addition, adults with ADHD often report

Rapid mood swings

Rejection sensitivity

Difficulties dealing with stressful situations

Persistent irritability

Emotional excitability (e.g., anger over minor things)

Relationship problems (e.g., short-lived, divorce)

Low frustration tolerance

ADHD & Gender Differences

The symptoms of ADHD present slightly differently in males and females. A list of differences is provided in the table below.

Psychological Sequelae: The Internalized Narrative

Children with untreated ADHD often experience repeated criticism—from parents, teachers, and peers—for behaviors perceived as careless, lazy, or defiant. Over time, this leads to internalized negative beliefs, such as:

“I’m not trying hard enough.”

“I always mess things up.”

“Something’s wrong with me.”

These beliefs can crystallize into shame-based schemas and perfectionistic or avoidant coping strategies in adulthood. Many adults with ADHD compensate through overachievement, hyperfocus on novelty, or avoidance of tasks that risk failure—patterns that can obscure the underlying condition.

Impact on Life

Adults with ADHD often experience the following:

Occupational challenges: Lower job performance, frequent job changes, unemployment.

Relationship difficulties: Higher rates of separation and divorce, parenting challenges.

Co-existing conditions: Increased risk of anxiety, depression, substance use disorders, and other comorbid conditions.

Substance Abuse: Numerous studies have shown that ADHD and substance abuse have a high comorbidity. That is, individuals with ADHD are at high risk of substance abuse in adulthood. This risk is significantly elevated if symptoms are left untreated. When ADHD symptoms are treated appropriately, the risk of substance abuse declines dramatically.

Academic issues: Difficulty in higher education settings due to challenges with focus, organization, and task completion.

Driving issues: More traffic violations, accidents, and revoked licenses.

Prevalence

Studies vary, but it's estimated that 2.5-5% of adults have ADHD. Many remain undiagnosed.

Challenges in Recognition

Adult ADHD can be under-recognized for a variety of reasons:

The hyperactivity component may decrease with age.

Symptoms can be mistaken for other disorders or life challenges.

There's a myth that children "outgrow" ADHD.

Common stigma that "everyone has ADHD"

Comorbidities

Comorbid conditions are common and can obscure diagnosis:

Mood disorders: Depression and bipolar disorders

Anxiety disorders

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Obsessive Compulsive Disorders

Substance use disorders

Sleep disorders

Learning disorders

Medical/Neurological Conditions: Narcolepsy, Traumatic Brain Injury, Dementia, Sleep Apnea, Thyroid disorders, Autoimmune disorders

ADHD vs Bipolar Disorder

Differentiating ADHD from Bipolar Disorder can be difficult because many symptoms overlap and both disorders often co-occur (that is, many patients have both ADHD and Bipolar Disorder). Below is a table that helps differentiate the two.

What is the Neuroscience behind ADHD?

Attention describes the process of determining the importance of various stimuli and selecting the one that's most relevant to the task at hand. Attention is an important component of our consciousness.

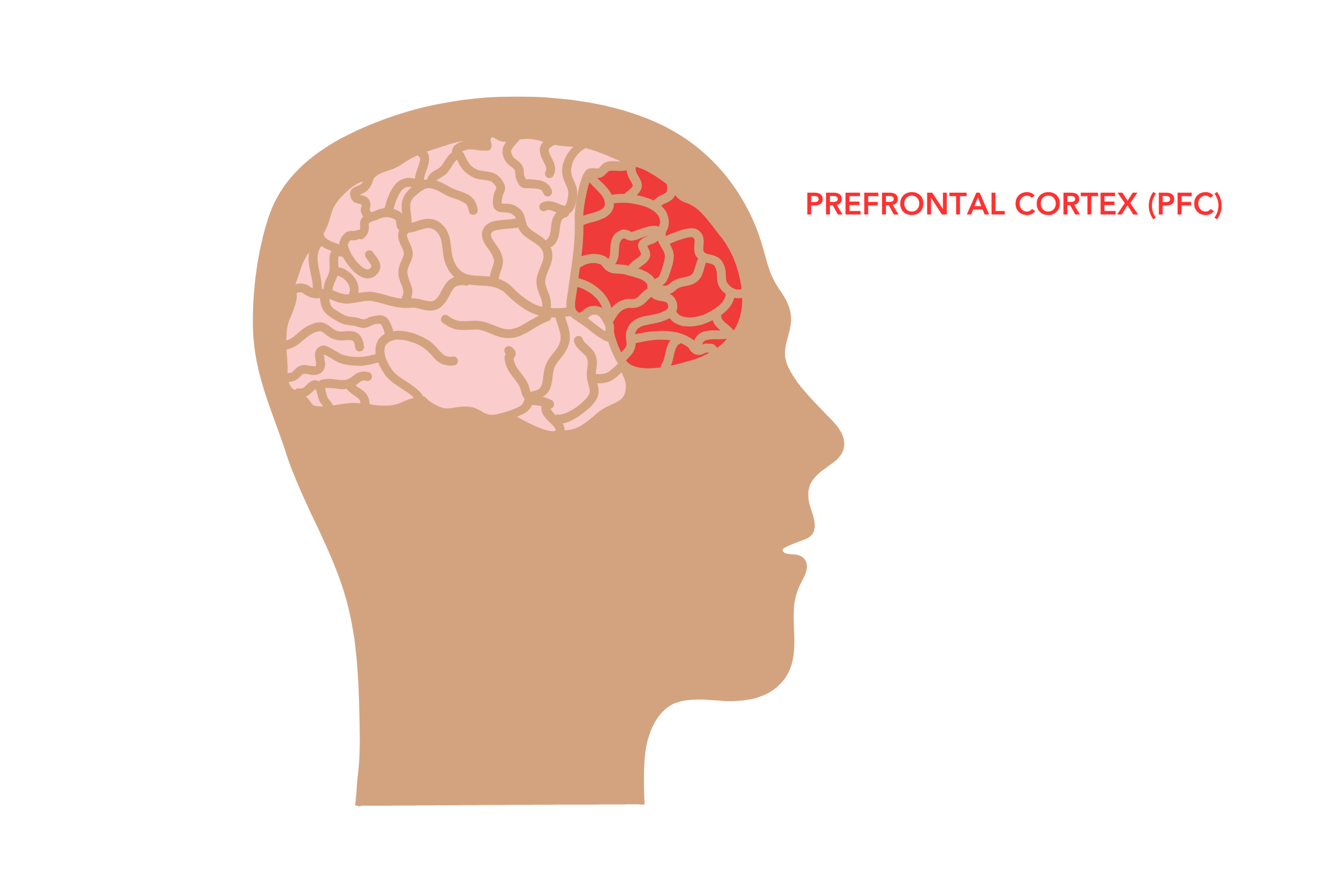

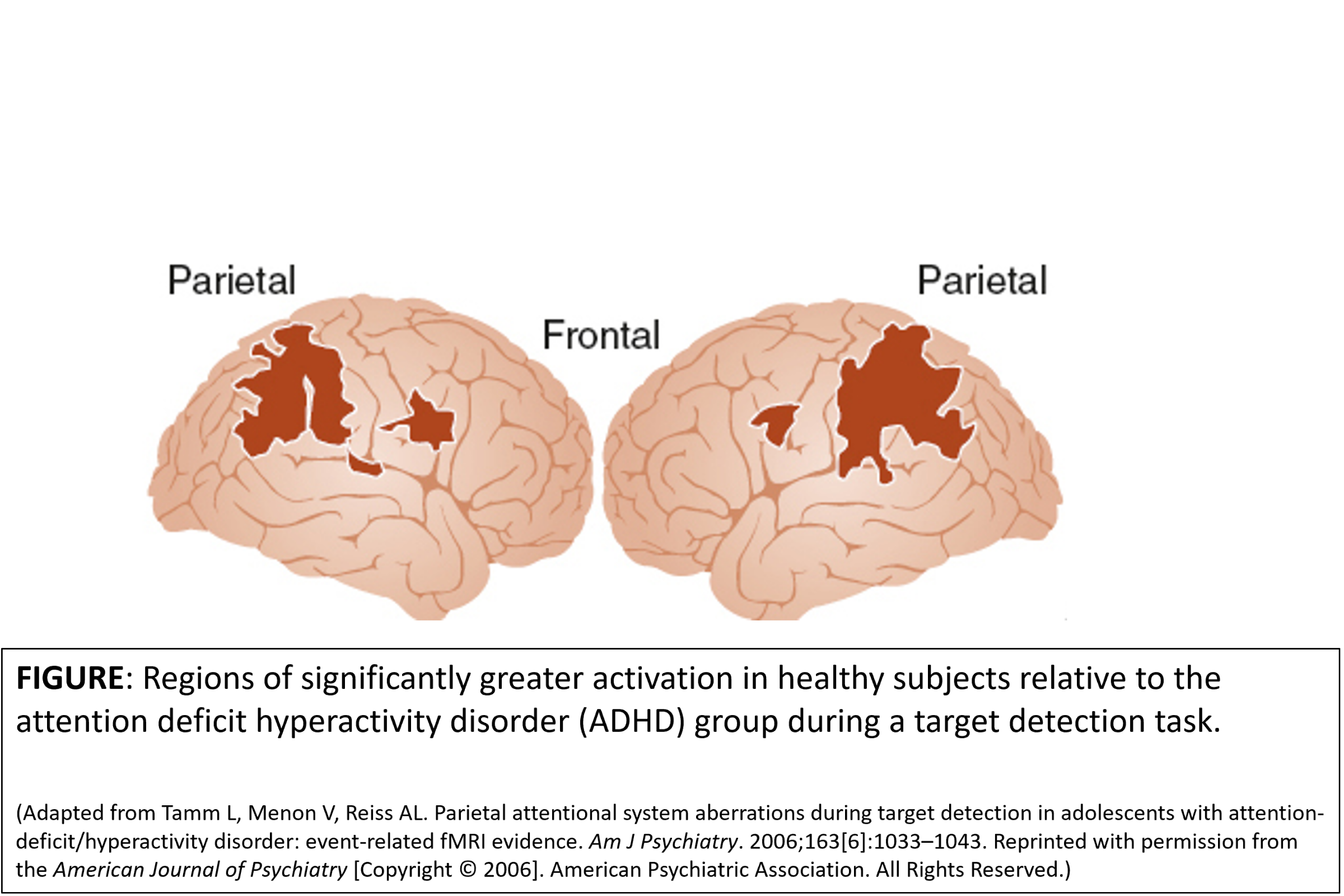

Although neural networks throughout the entire brain contribute to most brain functions, there are some areas of the brain that may play a greater role in attentiveness. These areas include the prefrontal cortex (which is part of the frontal lobe), parietal cortex, the cingulate cortex, and the striatum.

Cortico-Striatal Circuitry

ADHD involves altered signaling within fronto-striatal-thalamic loops:

Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC): executive function, working memory.

Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC): error monitoring, motivation.

Striatum (especially nucleus accumbens): reward anticipation and reinforcement learning.

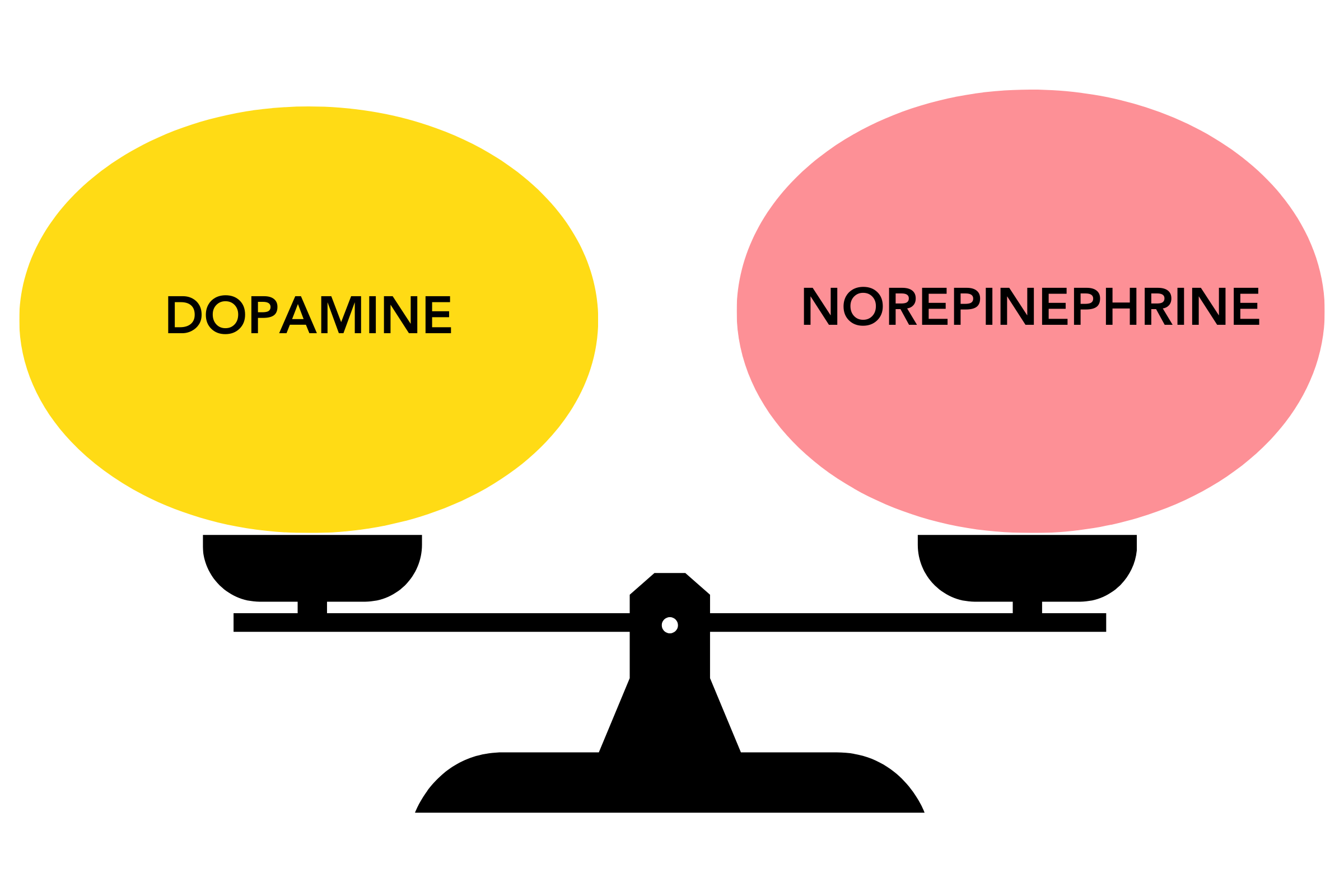

Dopamine and Norepinephrine Regulate Impulsivity

Dopamine and norepinephrine are two very important brain chemicals involved in attention, movement, and impulse control.

These two chemicals work together to "filter out" irrelevant stimuli while enhancing the relevant stimuli. In individuals with ADHD, these two chemicals appear to be imbalanced or "out of tune."

That is, when dopamine and norepinephrine signaling are suboptimal, the neural “gain” of relevant inputs is reduced—metaphorically, the brain’s “volume knob” for importance is turned down—resulting in distractibility, inattention, and inconsistent performance.

By enhancing these brain chemicals with medications and therapy we can improve symptoms dramatically.

Brain Changes in ADHD

Changes in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and an area called the striatum are the most common abnormal brain findings reported for ADHD.

Judith Rapoport’s National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) neuroimaging studies have revealed interesting findings in children with ADHD.

Children with ADHD, on average, have smaller brain volumes by about 5% and also have smaller cerebellums (the little brain in the back of the brain). Importantly, the trajectory of brain volumes did not change as the children aged, nor was it affected by the use of stimulant medication.

When comparing brain activity in children with and without ADHD, there was significantly greater activity in the parietal and frontal lobes of children without ADHD during an attention task. This tells us that decreased activity in the frontal and parietal lobes may partially explain inattentiveness. That is, these brain areas aren't activated enough during attention-requiring tasks.

How is ADHD Treated?

Medications

Medications remain the primary treatment for ADHD symptoms. Medications primarily target symptoms of inattention, mood reactivity, restlessness, ruminative-type anxiety, scattered thinking, and procrastination. Through a variety of mechanisms, medications help with filtering out extraneous external and internal sensory stimuli that are distracting and counterproductive in patients with hypersensitive nervous systems. Below is an overview of medications used to treat ADHD symptoms.

Psychostimulants (Amphetamines and Methylphenidates)

Methylphenidate and Amphetamine-based agents remain the gold standard. These drugs work by increasing the levels of certain chemicals such as norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin in the brain. Psychostimulant medications such as amphetamines (Adderall, Dexedrine, Vyvanse) and methylphenidates (Ritalin, Concerta, Focalin) are first line treatments for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder but are also helpful to alleviate symptoms of fatigue, low motivation, and concentration problems in patients with other psychiatric conditions.

Methylphenidates: Primarily inhibits Dopamine Transporters (DATs) and Norepinephrine Transporters (NETs), increasing extracellular dopamine and norepinephrine in the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) and striatum.

Amphetamines: Increase release of dopamine and norepinephrine from presynaptic vesicles in addition to reuptake inhibition.

Both effectively increase the signal-to-noise ratio in cortical networks, improving focus, working memory, and task persistence.

By enhancing dopaminergic tone in the striatum and PFC, stimulants correct the under activation seen in fMRI studies during sustained attention and executive tasks.

Modafinil (Provigil) and Armodafinil (Nuvigil)

While not classic stimulants, these medications primarily target histamine in the brain and are used to treat fatigue associated with narcolepsy and sleep apnea but are also used successfully in individuals with low motivation and attentional problems. These medications are less habit forming than dopaminergic stimulants like amphetamines and methylphenidates.

Nonstimulants (Atomoxetine, Clonidine, Guanfacine, and Bupropion)

These are usually considered when stimulants haven’t worked or have caused unacceptable side effects. Atomoxetine (Strattera) is one such medication that increases the levels of norepinephrine in the brain, which can help with symptoms of ADHD.

Atomoxetine (Strattera)

Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI).

Increases NE and DA (indirectly) in the PFC without significant striatal dopamine effect, reducing abuse potential.

Particularly useful in patients with comorbid anxiety or substance use risk.

Alpha-2 Adrenergic Agonists (Guanfacine, Clonidine)

Guanfacine (Intuniv) and clonidine (Catapres) are thought to modulate norepinephrine receptors in the prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain associated with attention and impulse control.

Strengthen prefrontal cortical regulation by inhibiting cyclic AMP signaling and “closing the gate” on irrelevant noise.

Often used adjunctively to reduce hyperarousal or improve sleep.

Bupropion (Wellbutrin)

Although not first-line treatment, Bupropion is an antidepressant used off-label for ADHD.

Bupropion is a Norepinephrine and Dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI).

Helpful in adults with ADHD and comorbid depression or nicotine dependence.

Click here to view a common MEDICATION ALGORITHM FOR ADHD

Behavioral Interventions

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Targets maladaptive thought patterns (“I’m lazy,” “I’ll never finish things”) and builds compensatory organizational systems.

Executive Function Coaching: Focuses on structuring routines, time management, and external scaffolding.

Mindfulness and Acceptance-Based Therapies: Improve attention regulation and reduce emotional reactivity.

Neurofeedback/Biofeedback has been shown to be helpful in improving attention and concentration in individuals with ADHD.

Regular exercise, sleep hygiene, a routine schedule, a structured environment, and a balanced diet can be beneficial.

These approaches address both symptom management and self-concept repair, fostering a narrative of competence rather than defectiveness.

Prognosis

With appropriate treatment and strategies in place, many adults with ADHD lead successful and fulfilling lives. However, untreated ADHD can have significant negative impacts on various aspects of life.

References

Arnsten, A. F. T., & Pliszka, S. R. (2011). The roles of dopamine and noradrenaline in the pathophysiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 69(12), e145–e157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.036

Shaw, P., et al. (2024). The dopamine hypothesis for ADHD: An evaluation of evidence. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 11604610. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.11604610

Riddle, M. A., et al. (2020). Unravelling the effects of methylphenidate on the dopaminergic and noradrenergic system in ADHD and its therapeutic implications. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 11, 7360745. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.00745

Heal, D. J., Smith, S. L., Gosden, J., & Nutt, D. J. (2013). Amphetamine, past and present – a pharmacological and clinical perspective. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 27(6), 479–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881113482532

Faraone, S. V., & Buitelaar, J. (2010). Comparing the efficacy of stimulants for ADHD in children and adolescents using meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 19(4), 353–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-009-0054-3

Volkow, N. D., Fowler, J. S., Wang, G. J., & Swanson, J. M. (2004). Dopamine in drug abuse and addiction: results from imaging studies and treatment implications. Molecular Psychiatry, 9(6), 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4001507

Chamberlain, S. R., & Robbins, T. W. (2013). Noradrenergic modulation of cognition: Therapeutic implications. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 27(8), 694–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881113490324

Biederman, J., Petty, C. R., Evans, M., Small, J., & Faraone, S. V. (2010). How persistent is ADHD? A controlled 10-year follow-up study of boys with ADHD. Psychiatry Research, 177(3), 299–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.12.010

Cortese, S., Adamo, N., Del Giovane, C., Mohr-Jensen, C., Hayes, A. J., Carucci, S., ... & Cipriani, A. (2018). Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(9), 727–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30269-4

Michelson, D., Adler, L., Spencer, T., Reimherr, F. W., West, S. A., Allen, A. J., ... & Dietrich, A. (2003). Atomoxetine in adults with ADHD: Two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Biological Psychiatry, 53(2), 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01671-0

Wilens, T. E., & Spencer, T. J. (2010). Understanding attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from childhood to adulthood. Postgraduate Medicine, 122(5), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2206

Surman, C. B. H., & Roth, T. (2011). Impact of ADHD and its treatment on sleep in adults. Sleep Medicine, 12(6), 578–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2011.01.014

Asherson, P., Manor, I., & Huss, M. (2014). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: Update on clinical presentation and care. Neuropsychiatry, 4(1), 109–128. https://doi.org/10.2217/npy.13.84

Wilens, T. E., Faraone, S. V., Biederman, J., & Gunawardene, S. (2003). Does stimulant therapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder beget later substance abuse? A meta-analytic review of the literature. Pediatrics, 111(1), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.1.179

Philipsen, A. (2012). Psychotherapy in adult ADHD: Implications for treatment and research. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 12(10), 1217–1225. https://doi.org/10.1586/ern.12.112

Philipsen, A., Jans, T., Graf, E., Matthies, S., Borel, P., Colla, M., ... & Hesslinger, B. (2015). Effects of group psychotherapy, individual counseling, methylphenidate, and placebo in the treatment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(12), 1199–1210. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2146

Kooij, S. J., Bijlenga, D., Salerno, L., Jaeschke, R., Bitter, I., Balázs, J., ... & Asherson, P. (2019). Updated European Consensus Statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD. European Psychiatry, 56, 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.11.001

Schoenfelder, E. N., Chronis-Tuscano, A., Strickland, J., Almirall, D., & Stein, M. A. (2019). Self-regulation and emotion dysregulation in adults with ADHD: An integrative framework. Clinical Psychology Review, 68, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.12.005

Philipsen, A., & Matthies, S. (2022). New psychotherapeutic approaches in adult ADHD: Acknowledging biographical factors. Journal of Neurology and Neurophysiology, 13(5), 450. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9562.1000450

Biederman, J., Petty, C. R., Woodworth, K. Y., Lomedico, A., Hyder, L. L., & Faraone, S. V. (2012). Adult outcome of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A controlled 16-year follow-up study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73(7), 941–950. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.11m07529

This article was reviewed by a licensed medical professional but is not personal medical advice. Please always consult a physician for any personal medical concerns.